|

Primer on Voting Rules |

|

|

The best voting rules are inclusive, well centered, and decisive.

The results can make a group more popular, stable and quick. |

| The concepts build from one voting task to the next: | ||

| Introduction | Tragedies of democracy: What's wrong? |

| Eras in Voting | Voting Progress: 19th Century, 20th Century, 21st Century. | |

| A Small Example | Nine voters: Line up to vote, Plurality, Runoff, Two issues. |

| Chief Executive | Instant Runoff Voting: Principle, Merits, Patterns. |

| Council Elections | Proportional Representation: Principle, Merits, Patterns. | |

| Project Selection | Fair-share Spending: Principle, Merits, Patterns. New |

| Budget Setting | Funding levels: Principle, Merits, Old Patterns. |

| Policy Decision | Condorcet & Rules of Order: Principle, Merits, Patterns. |

Philosophy. Philosophy.

Conclusions. Conclusions.

Prints. Prints.

Next Slide ↓ Next Slide ↓

| ||

|

After this primer shows the need for better voting rules, the voting workshop will show the simple steps in each tally. |

Introduction | ||

|---|---|---|

Tragedies of Democracy

| ||

|

|

Our defective voting rules come from the

failure to see there are different jobs for voting;

and these require different types of voting.

We all know how to decide the simplest sort of issue: A question with only two answers must be answered yes or no. For such an issue, “yes” and “no” votes are enough. But as soon as three candidates run for one office, the situation becomes more complicated. Then a yes-no vote is no longer suitable. Sometimes we do not want to elect just one official. We want a whole council to represent all the voters. For this we do not need a system that divides voters into winners and losers. What we need is a way of condensing them, in the right proportions, into their chosen leaders. |

Eras in Democracy | ||

|---|---|---|

The 1800s: Winner-Take-All Districts lead to Off-Center Councils

| ||

|

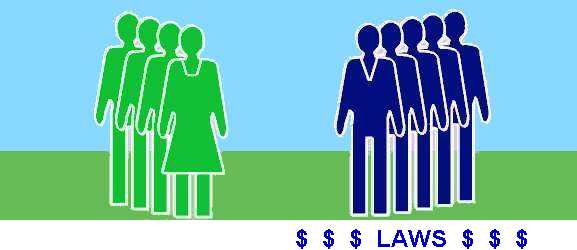

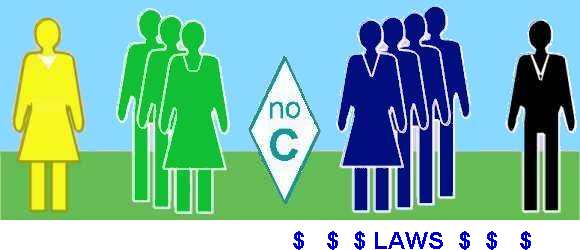

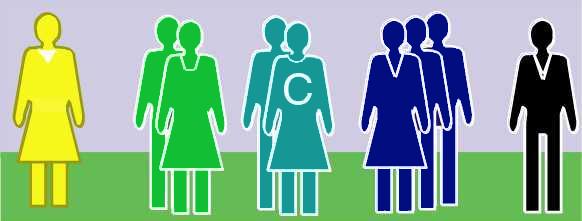

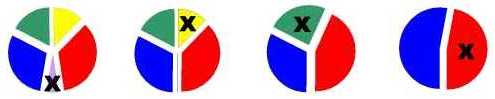

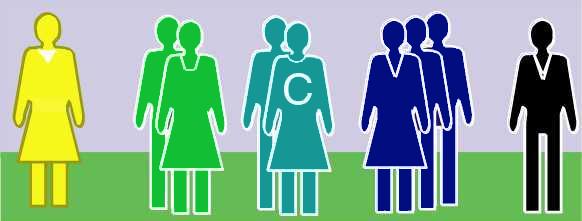

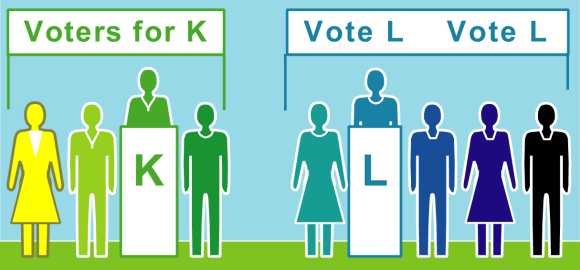

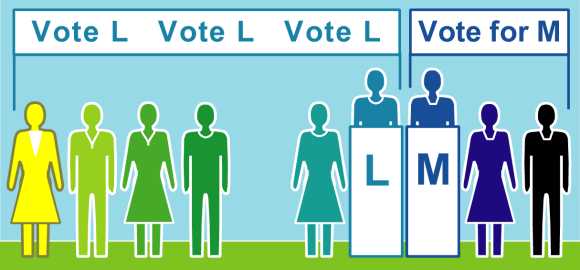

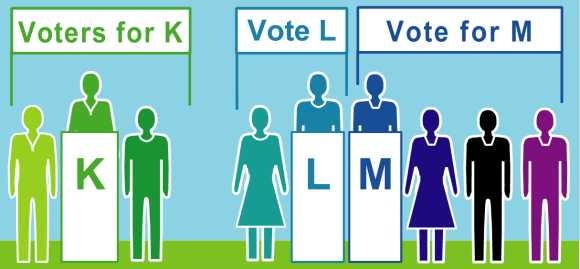

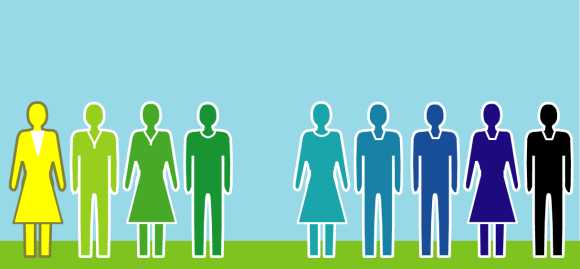

| Proportional Representation (PR) was invented in the late 1800s to end some problems caused by plurality rule. Most democracies have adopted PR. It elects several people to represent each large district. It gives a group that earns, say 10% of the votes, 10% of the seats. Thus PR delivers fair shares of representation. | It leads to broad representation of issues and opinions. But usually there is no central party (C in picture) and the two biggest parties normally refuse to work together. So the side with the most seats (blue and black) forms the ruling majority which then enacts — policies skewed toward their side. |

Typical Council Elected By Proportional Representation

2000s: Ensemble Councils lead to Broad, Centered Majorities

| New ensemble councils will elect most reps by Proportional Representation, plus a few by a central rule ( C in picture). Later slides show how a central voting rule picks winners with wide appeal and views near the middle of the voters. Its winners are thus near the middle of a PR council. | So they are the council's powerful swing votes.

Most voters in her wide base of support don't want averaged or centrist policies. They want policies to unite the best ideas from all groups. |

$

Ensemble Elected By Central And Proportional Rules

Democracy Evolves

Democracy Evolves

|

A “centrist policy” enacts a narrow point of view;

it excludes other opinions and needs.

A “one-sided policy” also ignores rival ideas. A “compromise policy” tries to negotiate rival plans. But contrary plans forced together often work poorly; and so does the average of rival plans. A “balanced policy” unites compatible ideas from all sides. This process needs advocates for diverse ideas. And more than that, it needs powerful moderators. | A broad balanced majority works to enact broad,

balanced policies. These tend to give the greatest chance for

happiness to the greatest number of people.

Excellent policies are a goal of accurate democracy.

Their success is measured by a typical voter's

education and income, freedom and safety, health and leisure.

An ensemble is inclusive; yet it is strongly centered and decisive. Voting rules for other tasks can follow this pattern. These will make the organization more popular, stable and quick. They are likely to avoid the one-sided results and tragedies at the top of this and other pages. |

Example | ||

|---|---|---|

Nine Voters

High taxes, great services Jump to the next slide by clicking the gray link. Plurality ↓ | ||

|

|

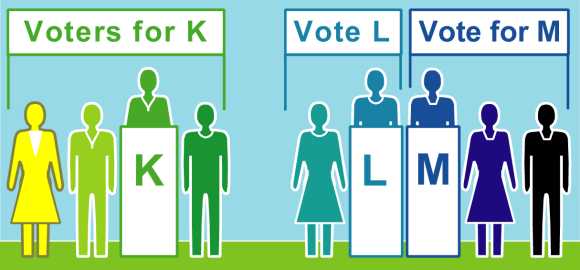

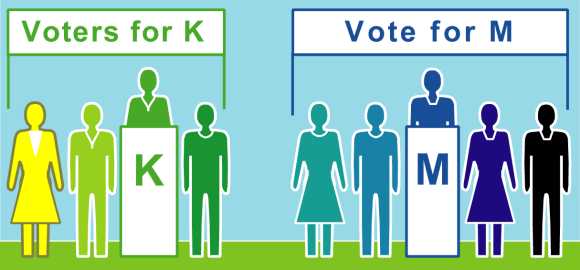

Three candidates stand for office. A voter

likes the candidate whose political position is nearest.

So voters on the left like the candidate on the left.

Ms. K is the candidate nearest four voters; L is nearest two and M is nearest three. Candidates L and M split the voters on the right. | Does anyone win a majority? Yes, No.

Who wins the plurality or largest share? K, L, M. Who wins the second-largest? K, L, M. Answers: Mouse over a question, but do not click. A mere plurality gives the winner a weak mandate. That is the authority voters give to winners. |

![]() K is nearest four voters.

K is nearest four voters.![]() L is nearest two.

L is nearest two.

![]() M is nearest three.

M is nearest three.

Runoff Election

|

Who wins a runoff between the top two? K, M.

The two who had voted for L now vote for M. Do votes that move count more than others? Yes, No. This winner has the power of a majority mandate. | Runoffs practically ask, “Which side is stronger?”

(We will look at this election more closely by using a voting rule that asks, “Where is our center?” The Proportional Representation rule below will pick several winners. It asks, “Which trio best represents all these voters?”) |

Candidate M wins the runoff.

Politics in Two Issue Dimensions

|

Voting rules behave the same when opinions

do not fit neatly along a line from left to right.

Here a group spreads out on two issue dimensions: left to right plus up and down. Perhaps on the steps of their school or state capitol, we asked | them a second

question about an issue unrelated to taxes and services.

“Please take one step up if you want more regulation. Take two steps down if you want much less regulation, and so on.” |

Kay wins a plurality.![]() Em wins a runoff.

Em wins a runoff.

Chief Executive | ||

|---|---|---|

The goal of Instant Runoff Voting is this:A majority winner

|

|

How does it work? You rank your favorite candidates,

as your first choice, second choice, third and so on. Then your ballot goes to your first-rank candidate. If no candidate gets a majority, the one with the fewest

|

Some benefits of Instant Runoff Voting are:

A majority winner from one election, so no winners-

A majority winner from one election, so no winners-

without-mandates and no costly runoff elections.

No hurting your first choice by ranking a 2nd, as the No hurting your first choice by ranking a 2nd, as the

2nd does not count unless the 1st choice has lost.  No lesser-of-two-evils choice, as you can mark your No lesser-of-two-evils choice, as you can mark your

true 1st choice without fear of wasting your vote  No spoilers, as votes for minor candidates move to No spoilers, as votes for minor candidates move to

each voter's more popular choices. |

Instant Runoff Voting Patterns

|

In South Korea's 1987 presidential election, two

liberals faced the aid to a military dictator.

The liberals got a majority of the votes but split

their supporters, so the conservative won under

a plurality vote-counting rule. These rules elect

whoever gets the most votes; 50% is not required.

The winner claimed a mandate to continue repressive policies. Years later he was convicted of treason in the tragic killing of pro-democracy demonstrators. With Instant Runoff Voting, ballots for the weaker liberal could have transferred to elect the stronger one. |

Instant Runoff Voting Patterns

From five factions to one majority.

| IRV elects leaders in cities large and small: London, Sidney, San Francisco, Burlington, Dublin and others. Students use it at Duke, Harvard, Stanford, Rice, Tufts, MIT, Cal Tech, Carlton, Clark, Cornell, Dartmouth, Hendrix, Reed, Vassar, Whitman, William and Mary, The University of: Cal, Il, Md, Mn, Ok, Va, Wa, Wi, and more. | A picture in the transferable vote workshop shows individual ballots moving.

IRV lets you vote for the candidate you really like. And even if that option loses, your vote isn't wasted; it goes to your next choice. |

Council | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

|

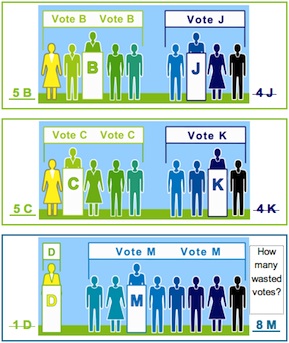

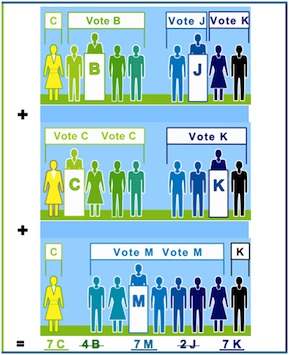

That is, 60% of the vote gets you 60% of the seats,

not all of them. And 10% of the vote gets you 10%

of the seats, not none of them. These are fair-shares.

How does it work? There are three basic ingredients:

|

Some Benefits of Proportional Representation:

It gives each major group a fair share of reps; so it It gives each major group a fair share of reps; so it

often elects more political minorities and women.

|

Fair Shares and Moderates

| Chicago now elects no Republicans to the State Congress, even though they win up to a third of its votes. But for over a century Chicago elected reps from both parties – because the state used a good rule to elect three reps in each district. Most districts gave the majority party two reps and the minority party one. | Those Chicago Republicans were usually moderates. So were Democratic reps from Republican strongholds. Even the majority party in a district tended to elect more independent- minded reps. Working together, they moderated the state's policies. |

Fair-Shares and Moderates 2

|

New Zealand switched in 1996 from Single-Winner

Districts to a blend of SWD and Full Representation.

A one-winner district exaggerates local issues and alliances.

Full Rep frees voters from district enclosures to

elect some reps with thin but widespread appeal.

The number of women elected rose from 21 to 35. The number of native Maoris elected rose from 6 to 15, which is almost proportional to the Maori population. Voters also elected 3 Polynesian reps and 1 Asian rep. Many people call this Proportional Representation or Proportional Voting. (The transferable vote workshop shows one way to get Full Representation.) |

Projects | ||

|---|---|---|

Fair Shares to Buy Public Goods

$

| ||

|

|

Membership groups often shirk competitive elections

to avoid conflicts and hurt feelings. But members

still compete over money to fund projects.

Sometimes a group uses tricks to capture a lot of the budget. When that injustice is felt, other groups may grow rebellious, or leave. They need a rule to make funding fair and accurate. |

![]() Many empty hands

Many empty hands![]() Fair Shares

Fair Shares![]()

A System of Unfair Spending

|

“...[E]armarks [are] the devices by which individual

members of Congress set aside budget resources for

pet projects in their districts. This year House members

have requested nearly 19,000 of these programs...

If all were approved, the total cost would amount to $279 billion...”

Washington Post, Sunday, July 8, 2001; page B6

Under old rules, senior reps give several times more “pork” spending to their districts than junior reps do. Voters can't easily see who's responsible for a project. And reps must vote on omnibus bills that include many projects, some good, some bad. |

The principle of Fair-share Spending is this:

Spending power for all,

in proportion to their votes.

|

That is, 60% of the voters spend 60% of the money,

not all of it. A project still needs grants from many

voters to prove it is a public good worth public money.

So we let a voter fund only a fraction of a project.

How does it work? Like IRV: You rank your choices. Then your money moves to help all the favorites you can. And a tally of all ballots drops the least-funded project.

|

Merits of Fair-share Spending

It lets sub-groups fund projects; it's like federalism,

It lets sub-groups fund projects; it's like federalism,

but without new layers of taxes and bureaucracy. It funds big groups, whether spread out or local.

* FS can set the budgets of departments too. Each

|

Participatory Budgeting

|

In a citywide vote, each neighborhood or interest

group funds a few school, park or road improvements.

The city's taxes then pay for the projects as the School,

Park, and Road Departments manage the contracts.

Every neighborhood and interest group controls its share of spending power; no one is shut out. This makes (hidden) empires less profitable. |

Fair-shares or Winner Take All

|

If a plurality spends all the money, the last thing they

buy adds little to their happiness. It is a low priority.

But that money could buy the high-priority favorite of

a large minority; making them happier.

In economic terms: The “social utility” of the money and goods tends to increase if we each allocate a share. Shares spread opportunities and incentives too. In political terms: Fair shares earn wide respect, as we are each in a big minority wanting some project. The budget serves and appeals to more people. (The transferable vote workshop outlines a simple tally.) |

Budgets | |

|---|---|

Setting Agency Budgets |

|

Fair shares can set the budgets of departments too.

Each funding level of each department is like a project. To win, it needs to receive a number of votes. It gets one from each ballot currently sharing the department's cost up to that level or higher. Each agency starts with [80]% of its recent budgets.*

* To vote less than that to basic services, such as the

|

More Merits of Fair-Share Spending

Smooth budget roller-coasters that hurt efficiency. Smooth budget roller-coasters that hurt efficiency.

Fix starvation budgets designed to cause failure. End hidden empires taxing powerless minorities.

|

Notes on Merits of Fair Shares

The “in-group” at a college, club, co-op, condo, or The “in-group” at a college, club, co-op, condo, or

congregation cannot take more than their fair share; nor give the “out groups” less than their shares.

(The transferable vote workshop shows budget-setting math.) |

Old, Black-Box Budget Rules

|

The current budget process blurs responsibility.

Take deficit spending. Liberals may say the main

cause is excessive military spending; conservatives

often say it's social services. Every rep can claim,

“I didn't spend too much.”

Protecting the environment is popular with both conservative and liberal voters. Reps don't dare attack it openly. So, to pay off some corporate donors, reps slyly starve agencies that enforce environmental laws. Similar cuts have hit OHSA and the auditors of corporate tax returns. |

Old Roller-coaster Budget Patterns

|

“Because research may take decades to flower, lower but constant

funding is more productive than a roller-coaster budget that

might average far more, says Alvin W. Trivelpiece, director of

the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.” BusinessWeek: 5/26/97

Members might be more cautious about starting vast projects if they could not spend the opposition's share of the budget. And they should have the power to finish their projects with their own share.

Everyone can see a rep's grants.

|

Old Budget Refill Voting has:

Majority rule,

within a balance of forces.

|

So if we all agree, we can change budgets radically.

But if many disagree, they can moderate the changes. Yet a minority cannot slow the budget process. Each agency starts with [80]% of its current budget.

A minority can moderate a budget's change.

BRVa lets a majority reduce their grants to agency X to undercut a minority's grants to X. So, to maintain the total for X, the minority must give it bigger grants. Then the majority reduces theirs, etc. With BRVa, nobody apportions the budget as they sincerely want it. In contrast, the previous fair-share rule gave all members positive power to fund favorites. |

Policy | ||

|---|---|---|

Pairwise Test Number Two

K is nearest four voters. | ||

|

| Candidate L wins her next one-on-one test also. She has won majorities against each of her rivals, so she is the candidate who best represents all the voters. She is the Pairwise winner. | Could another person top candidate L? Yes, No.

Hint: Is anyone closer to the political center? Yes, No. Who is the Pairwise winner on page 9? K, L, M. Thus Pairwise picks a central chairperson or policy, but probably not a dynamic CEO, or diverse reps. |

![]() L is nearest 6 voters; M is nearest 3.

L is nearest 6 voters; M is nearest 3.

The principle of the Pairwise Tally is this:

Majority victories

over every single rival.

|

Option M beats option K if most voters rank M above K.

Each ballot's rank of M relative to K concerns us.

Their numbers of first-rank votes do not. The winner must beat every rival, one-against-one. If another rule picks a different winner our “round-robin” tournament, or Condorcet winner ranks higher on most ballots, so she wins a one-against-one majority over that other rule's winner. |

Pairwise Tallies Quickly Pick Balanced Policies

Full-choice ballots rank related motions all at once. Full-choice ballots rank related motions all at once.

They simplify the rules of order and speed up voting. They cut down agenda affects including poison-pill and free-rider amendments.

|

Pairwise Popularity and Balance

| A policy needs good marks from voters all along the political spectrum. That is because every rep can rank it relative to other policies. So all voters are “obtainable” and valuable. This leads to policies with wide appeal. (A plurality or runoff winner gets no help from the losing side and doesn't need to please those voters.) | The Pairwise winner is central and popular: Most centrist and liberal voters prefer it over each conservative policy. At the same time, most centrist and conservative voters prefer it over each liberal policy. All sides can join to beat narrowly-centrist policies. |

Everyone helps choose our center.

A Moderator's Balanced Support

|

Most liberal voters rank Kennedy [Livingstone, Lafontaine]

above Clinton [Blair, Schröder]. So to win a majority over

Kennedy, Clinton must outrank him on ballots from

centrists and conservatives. She cannot hope to be the first

choice for conservative voters; still, she must seek their favor.

Conservative voters rank Bush [Major, Kohl] higher than Clinton. So to win a majority over Bush, Clinton must appeal to centrists and liberals. | Every candidate needs the centrists voters, of course. But

every candidate needs the liberals and conservatives too.

When compared with Kennedy, Clinton needs those

conservative voters. And when compared with Bush,

Clinton needs the liberals.

In this Pairwise election of a moderator, a less controversial candidate might top each of these polarizing politicians. |

Gerrymander

| Candidate M lost the last election by plurality rule. Now let's say her party gerrymanders the borders of her election district. They add neighbors (purple below) who tend to vote for her party, and exclude less favorable voters. So now her party is certain to win the new district. | The old plurality rule is the easiest to manipulate. But the Pairwise winner, L, doesn't change in this case. And Proportional Representation also resists gerrymanders. |

![]() Now K has 3 votes.

Now K has 3 votes. ![]() L has two.

L has two.

![]() And M has four.

And M has four.![]()

Bribes

| Bribes, big campaign gifts, and jobs for friends

can make some reps switch sides on a policy.

Pairwise resists corruption well, as bribing a few reps

moves the council's middle, and the winning policy, only a little.

“Poison-pill amendments” are designed to make some reps change sides and oppose a bill they had supported. Pairwise lets reps rank the original bill, no bill, and the (poison) amended bill. They may shun the pill. Fair shares of seats and spending reduce the payoffs

to those who bribe the biggest party. It can no longer

seize more than its share of reps or money.

(The transferable vote workshop shows a Pairwise Condorcet tally.) |

Philosophy | |

|---|---|

Why Vote

| |

|

|

Groups with little time and many issues or many

members and conflicting interests, usually follow

discussions with voting rather than consensus.

Voting can be anonymous to protect dissidents. It provides equality for busy or unassertive people. Pondering a ballot or survey educates members about setting budgets and priorities. A straw poll can find the major opinion groups and focus a discussion on the strongest idea from each group or on the most central options. Some issues allow decisions that are not adversarial or consensual: Multi-winner funding gives everyone a fair share of power — without letting anyone dictate or block action. |

Exit or Power

|

Ultimately, voting cannot satisfy two people with

opposing values. Leaving or “voting with your feet”

is the surest way to get to the policies you want.

When you can't do that, avoid willful authoritarians;

build democratic institutions with open-minded

egalitarians.

Democracy improves in eras such as The Enlightenment. Many people restrained blind faith, obedience and ideology. They worked to expand knowledge through rational, skeptical and empirical thinking. (There's more on the democratic philosophy page.) |

Tools Between People

Tools Between People

|

Voting rules affect our laws — and our views on life.

By making us practice winner-take-all or sharing, rules change the way we treat each other and see the world. Fair-share rules can shift our expectations of voting and government. They can move from tools for fighting culture wars toward tools supporting diversity and its freedoms. Voting reforms are a gateway to many popular changes. Then shifts in power will be small, frequent and normal. Happiness for most people is strongly linked to good relationships. So a good way to increase happiness is to improve Tools Between People. |

Steering Analogy

|

When choosing a voting rule, a new Mercedes costs

little more than an old jalopy. That price is a bargain

when the votes steer important budgets or policies.

Does your car have an 1890 steering tiller or a new, power steering wheel? Does your organization have an 1890 voting rule or a new, centrally balanced rule? Today's drivers need the skill to use power steering — but they don't need the math or logic to engineer it. Same with voters and voting rules. A group may test drive a new rule in a survey, or by turning into a “committee of the whole” to vote, tally and report its result, to enact by their usual rules. (The call for a survey or report might bar amendments to it, so a majority cannot cut a minority's power.) |

Conclusions | |

|---|---|

Better Election Rules

|

Give voters real choices of candidates who can win,

Give voters real choices of candidates who can win,

by electing fair shares of reps from all big groups.

|

Some Benefits of Legislative Rules

Give fair representation to all major groups;

Give fair representation to all major groups;

so the council will enact laws with real majorities.

|

Related Issues

|

Ballot access laws make it hard for minor parties to get their candidates on the ballot. The two big parties make those laws largely because they fear spoiler candidates. Better voting rules put that fear to rest.

News firms might inform us better if they were ruled by the subscribers' votes. Public campaign funding, as in Maine and Arizona, lets reps give less time to rich donors and more to common voters. (The Ackerman- Ayres plan lets each voter give anonymous vouchers.) Optical-scan ballots and open-source software check fraud by election workers and corporations. Sabbatical terms make the current rep run against a former rep returning from sabbatical. Voters get a real choice between two winners. Each has a record of what they did when elected. Plurality would tend to make the current and former reps both lose due to a party split. But IRV and Pairwise heal party splits. Initiative voters get more choices and power with full-choice ballots and Pairwise tallies. They should set the political rules. But minority rights to ballots, reps and funds need constitutional protection from the majority of the day. |

Conclusions

|

Many people are excited to learn that voting

does not have to mean 'winner take all'.

The best voting rules are fast, easy and fair.

This page shows that different voting tasks need different kinds of voting rules. |

Actions

|

Learn more in this e-book, Accurate Democracy.

Then build support in your school, club or town with FairVote, The Center for Voting and Democracy. Steps toward accurate democracy include:

Accurate Democracy.com has simulation games and handouts plus free ballot-entry and tally software. |

Booklets, Flip Charts, and Slide Shows

| Booklet size | Grade | Primer | Workshop | Font | Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pocket B&W | 9-12 | doc pdf | doc pdf | 10 | letter a4 |

| Paperback | 10 up | doc pdf | doc pdf | 10 | legal b4 |

| Hardback | 12 up | doc pdf | doc pdf | 13 | letter a4 |

| Legal | 11 up | doc pdf | doc pdf | 24 | legal b4 |

| Flipchart | 11 up | doc pdf | doc pdf | 36 | legal b4 |

| Slides | 11 up | ppt html | ppt | 26 | screen |

| " Outline | 11 up | ppt | ppt | 32 | screen |

|

The B&W pocket primers print well on black-ink printers.

Workshops can print on A4 letter paper (no cuts or folds) with plain columns: doc, pdf;

or a more colorful style: doc, pdf.

Mail Order: Prices include shipping in the USA or Canada.

If you prefer more numbers and logic with fewer pictures, the original Democracy Evolves is again free to browse or print: doc, pdf. Its 8 pages in B&W supplement this Primer.

This is “open source” writing, so edit the slides as you will and add your own slides for other topics. For example, U.S. voters need concise statements of the principles and benefits in non-partisan redistricting, as practiced in Iowa, and public campaign funding, as practiced in Arizona, Maine, or North Carolina. You may want to skip some topics or change the wording to suit an audience. For legislators you might change “voter” to “rep” or “member” and you would do the opposite for a direct democracy. The latter might omit Instant Runoff Voting but keep Full Representation to select subcommittees. Thanks to Steve Chessin for writing the original version of the “elevator pitch” for Full Representation. He, Terry Bouricius, and Zo Tobi each wrote quick pitches for Instant Runoff Voting which were the basis for the IRV slide above. Overall editors include Tree Bressen, Cheryl Hogue, John Richardson, and Rob Richie. Many others have contributed ideas and writing.  Navigation: This page showed the need for better voting rules and their merits. The next page, a voting workshop, shows the simple steps in each tally and how they meet their goals. After that, you may want to read the one-page introduction to each of the six voting tasks. These tell how a task is like and unlike other uses of voting, what it must do, stories of tragedy and success, the best rule's name, its ballot and its main merits. Accurate Democracy is organized by uses of voting:

|

|

Voting for rich men, poor men, “colored” men, women.

Voting for rich men, poor men, “colored” men, women.

Accurate Democracy

Accurate Democracy